Roark: Local rivers were early interstates

Published 10:53 am Monday, February 12, 2024

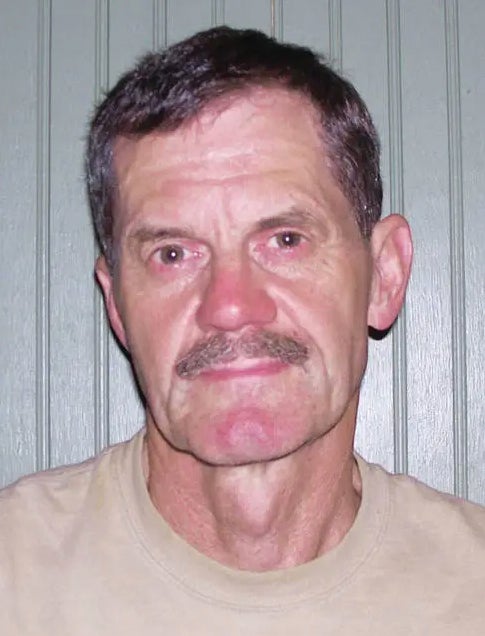

- Steve Roark

|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

By Steve Roark

Contributing Writer

In the early and mid-1800s, the industrial age and a growing population created a high demand for raw materials to make products, especially wood and metals such as iron and lead. Our area had metal ore deposits to produce pig iron in locally owned furnaces fueled by wood charcoal and coke. Pig iron needed to be shipped to big cities like Chattanooga, where it was refined and made into metal products such as tools and farm implements. Our area also had vast forests to provide wood for a housing-hungry nation, but timbered logs needed to be shipped to large sawmills for processing into lumber, and again, Chattanooga was the closest place. Both pig iron and logwood were heavy and costly to transport long distances by wagon roads, and railroads didn’t come into play until almost the end of that century. The problem was resolved using another natural resource, rivers.

All local rivers (Clinch, Powell, Holston, French Broad) form the headwaters of the Tennessee River, which flows by Chattanooga, providing a means to get raw materials to markets wanting them. A flowing river provided the energy to move things down it, so there was no need for sails, just the ability to steer. Materials such as pig iron, barrels of salted pork, furs, and corn liquor were transported on watercraft called flatboats, which were perfect for use on small rivers. They were single-use, simple structures made from local lumber. When they reached Chattanooga, they were dismantled, and the lumber sold. They were very buoyant, capable of hauling 30-40 tons for cargo, and they were maneuverable using long steering oars and capable of navigating narrow and curvy sections of river.

The downside of using small rivers for transportation is that they could only be used during high water flow, which generally occurred in late winter and spring during high rainfall and snowmelt periods. This created hazardous conditions for the boatmen, who had to maneuver a heavy boat in fast-moving floodwater around steep curves, submerged and downed trees, and islands in cold, wet conditions. Many died from exposure.

Transporting timbered logs had the same challenges and hazards as flatboats, but the logs themselves were lashed and spiked together to construct large rafts. They were 25 feet wide and 80-100 feet long and were maneuvered using long oars and poles, again no easy task in cold-wet conditions. My grandfather, Tommy Roark, cut timber in Claiborne County, Tennessee, and floated logs to Chattanooga, some 200 miles.

Once the flatboats or log rafts made it to Chattanooga (a seven to 12-day trip) the cargo was sold and the boatmen either walked or bought a horse and made the several day’s journey back home.

Our ancestors were tough, innovative, and able to use local raw materials and resources on hand to create several local industries. Wood, metals, rivers, and mechanical power from mountain streams provided jobs and products to help build a young nation.

Steve Roark is a volunteer at Cumberland Gap National Historical Park.