Harlan County turns 200

Published 10:39 am Monday, April 1, 2019

By James S. Greene III

Contributing Writer

On April 1, Harlan County is 200 years old.

What this means is that Harlan County as a political unit and cultural construct is that old; however, the history of modern Harlan County begins with the movement of people of European origin along with, in many instances, the people of African origin whom they held enslaved into southwest Virginia and Kentucky during the second half of the 18th century. As these people moved westward, they imposed lines on the landscape; lines to define their property and lines to define their units of government so that for many years, Harlan County was part of much larger jurisdictions than it is today.

In 1772, it lay within Fincastle County, Virginia, which ran from east of present day Radford to the Mississippi River and included much of today’s West Virginia and all of modern southwest Virginia. In 1776, Fincastle was divided into three counties: Montgomery, Washington and Kentucky. Washington encompassed today’s Washington, Russell, Scott, Lee and Wise counties. This territory was home to a large number of early Harlan County settlers before they emigrated here. Kentucky County contained what later became the 15th state.

In 1780, Kentucky County was divided into Jefferson, Fayette and Lincoln counties, with Harlan being part of the latter. In 1799, the southeastern corner of Lincoln was cut off to form Knox, and in 1819, the eastern end of Knox became Harlan. For years after Harlan County was formed, it took in much more territory than it does at present. The people who lived within those bounds thought of themselves as Harlan Countians, though where some of them lived is now part of Letcher, Bell or Leslie counties.

In telling this story, we acknowledge that fact with the use of the term “greater Harlan County.”

Harlan County’s history is tied intimately to its geography, especially to the parallel mountain ranges that run northeast to southwest across the county: the Cumberland-Stone Mountain range, the Little Black and Black mountains, and Pine Mountain. These ranges are part of a much larger system extending into southwest Virginia and northeast Tennessee including Wallen Ridge, Powell, Clinch and Bays mountains. Gaps in these mountains became the pathways through which westward traffic would flow. The gaps most crucial to the early explorers and settlers were Big Moccasin Gap near present day Gate City, Virginia; Pound Gap; and Cumberland Gap. By virtue of the water gap through Pine Mountain at Pineville, Cumberland Gap became the principal conduit for those people seeking the riches of central Kentucky from the south. Using the Gap, most early Kentucky settlers bypassed the rugged terrain that is now Harlan County. However, the Cumberland and Stone Mountain range has a number of lesser gaps that gave determined hunters and explorers direct access to the headwaters of the Cumberland.

What attracted these hunters to the greater Harlan area was the rich variety of animal life. At that time, Harlan was home to buffaloes, bears, elk and deer, otters, mink, beavers, foxes, wolves and panthers. Most of these species had a definite economic value, making the effort to hunt and kill them a means of earning a living. So, beginning in the 1760s, the area began to be visited by hunters, including some of those associated with the famous “long hunts” of the period.

In 1761, a group of men led by Elisha Wallen penetrated the southwest Virginia-northeast Tennessee area just south of Harlan. Some of them may have crossed into the county at that time. In subsequent years, several of these same men and others made additional extended hunts that took them into Kentucky through Cumberland Gap and up and down the Cumberland River as far as Nashville. In 1769, one of these hunters left his name or part of it, Willia Wea, and the date carved on a beach in the valley now occupied by the city of Harlan. Other trees with his name were found much further down the river below the falls. Another early hunter whose range included Harlan County was William Carr, originally of Albemarle County, Virginia. Carr was biracial, the product of an extramarital affair between his white mother and a black man; his mother’s husband accepted him as a son, saw that he received an education, and when he turned 18, gave him a rifle and a horse and sent him west to make his way. “He hunted beyond the Cumberland mountain to the right of the gap in a place called the brush,” recalled one of his contemporaries. “[H]e described the game as being very gentle and would scarcely flee from the report of a gun.”

The Long Hunters typically set up a base camp and then fanned out in twos and threes, partly to keep a low profile from Indians who might also be hunting in the region and not welcome the competition (the Indians also knew the value of pelts and skins) and partly to avoid overhunting any one particular spot. The primary quarry for these hunters were deer whose skins had great commercial value and could be packed and transported more readily than buffalo or bear skins. Deer were typically hunted during the summer and early fall; after first frost, physiological changes occurred in the animals that made the skins less valuable. During the winter, the focus moved to pelts such as beaver, mink and otter. The hunters made jerk for themselves from deer; smoked bear meat and turned the fat into tallow. In connection with the processing of their kills, they built racks for smoking the meat or sometimes “skin houses,” typically partially open pole houses roofed with bark where they dressed and stored their furs. Some of these hunters brought a slave with them to assist them; Elisha Wallen, for example, owned a man named Jake.

As they moved through the mountains, they left their names on geographical features of the land. Elisha Wallen and other members of his family figured prominently in the exploration of the region. The extent of their ramblings can be tracked by the places where they left their name: Ridges in Virginia and Kentucky and creeks in Lee County, Claiborne County and Harlan County. While hunting in the vicinity of Wallins Creek in Harlan County, a party led by Thomas Wallen, Elisha’s brother, was attacked by Indians. This attack, according to one source, resulted from the shooting of a lone Indian earlier that same day. Another source states that it was in revenge for the killing of a relative of the Cherokee chief John Watts in present day Hancock County, Tennessee. The Indians allegedly had called Wallen out by name and tried to capture his wife. Watts and his men followed the Wallen party to Kentucky. The sources agree that the Indians killed seven men. According to Hiram Roberts, “they were some of his boys who were killed.” According to James Brock, Wallen himself was killed along with six others; only one of the party escaped. When he brought others back to bury the men, they found that the hunters’ dogs had torn apart all the bodies except for Wallen’s; his dog kept guard beside him. According to Brock, the incident occurred on Laurel Branch a short distance beyond the mouth of War Branch.

John Benham came to southwest Virginia from Maryland, bringing with him a variety of apple known along the Potomac as ‘the marshmallow apple’ but destined to fame in the mountains as the Benham. Described as “a noted Indian fighter, hunter and farmer,” Benham settled on the north fork of the Holston near present day Mendota, Virginia in 1769. A land entry made by John Latham in 1782 includes “Bennums Camp.” This tract was located on Clover Fork on a creek near a rock house. Oral tradition says that while hunting and prospecting for ginseng (most likely from this camp), one of the Benham family fell victim to a panther attack. His hunting companion, whose last name was Brody, buried him in the vicinity of the present site of Benham, digging the grave with a tomahawk.

Joseph Martin, another Albemarle County native, was as a youth somewhat restless and wild. After running off as a teenager to join the army in the French and Indian War, he returned, married and settled in Orange County. In debt, due in part to his fondness for gambling, he entered the fur trade as a way to reverse his fortunes. He is said to have accompanied Wallen on the first long hunt in 1761. During most of that decade, he went out annually for six to eight months at a time always returning with a sizeable number of pelts. It is possible that Harlan County fell within his hunting grounds and that is when his name got attached to Martins Fork.

However, a more likely explanation comes from his involvement in the beginnings of settlement in Powell’s Valley. In 1768, Dr. Thomas Walker of the Loyal Land Company, also from Albemarle County, proposed that Martin assist him in settling the area on the Virginia side of Cumberland Gap. A letter written by Martin in 1769 recounts a competition between his party and another group. Whichever group got there first would receive huge tracts of land, and the other group would be excluded. The exact number in Martin’s party is not known; one account suggests five or six and another as many as 20 or 30. Even though they got lost for a couple of days, the Martin party arrived first, winning the contest, and starting what became known as Martin’s Station. The site of the station near present day Rose Hill, lay directly across the Cumberland Mountain from southwestern Harlan County; the first significant watercourse one would strike on crossing the mountain is Martins Fork, which suggests that Martin and his men used it to travel into the Cumberland Valley. The settlement lasted only a few months as the Cherokees, encouraged by the British Indian agent to rob settlers rather than kill them, used a ruse to keep Martin and his men out in the countryside while they robbed the station and destroyed their work. Martin restarted the station in 1775 at the time of the Transylvania settlement of Kentucky, but with the outbreak of the Revolution, it was too exposed and was again abandoned, not to be reoccupied until 1783.

Other hunters also left their names on the landscape. Crank’s Gap, an important point of entry to the county in the early days, bears the name of John Crank, a French and Indian War veteran who settled in 1774 in Fincastle County on Copper Creek and Moccasin Ridge. Drury Puckett, also a French and Indian War veteran and Fincastle resident, gave his name to Puckett’s Creek — which also known in the early years as Coxes Creek, most likely named for Charles Cox, an associate of Elisha Wallen’s and one of the Long Hunters. Members of southwest Virginia’s Looney family left their name on ridges and creeks on both the Kentucky and Virginia sides of the mountain.

The first known written record of a visit to Harlan County comes from members of a family that would become prominent in Kentucky affairs in the early years of statehood. Three brothers, James, George and Robert McAfee, along with their brother-in-law, James McCoun, and a teenaged neighbor, Samuel Adams, came to Kentucky in the summer of 1773. Having heard talk back in Botetourt County about “the rich and delightful country to the west,” they decided to come see for themselves and locate land on which to settle. They took the Ohio River to the mouth of the Kentucky and then followed the Kentucky to the present site of Frankfort. From there, they headed towards the Salt River and what is now Mercer County where they surveyed a number of tracts for themselves. Thinking it would be a more direct route home, they chose to head up the Kentucky and cross the mountains into Powell Valley where they could pick up the long hunters road. On Aug. 11, they reached Leatherwood Creek at which point they left the Kentucky and traveled in a direction that brought them to Pine Mountain which they crossed on the 12th. Striking Poor Fork near its junction with Clover Lick Creek, they went up the latter coming to the salt licks for which it would later be named. They took one of the paths made by elk and started up Big Black Mountain. That night they camped on the headwaters of Clover Fork and crossed Stone Mountain on the 13th, striking the Powell River near present day Dryden. On the 15th they came to a house “which,” wrote Robert, “was a glad sight to us. The following day they reached the house of an acquaintance where they spent several days recuperating — “Our feet were much scalded and so lame that we could not travel,” wrote James — before continuing home to Botetourt.

Their journal entries constitute the earliest known description of Harlan County. James wrote: “August 12th. Thursday. We travelled through the laurel hills six miles further and struck a large creek at a big fork at the falls of it, we took the south fork in about two miles we came to some big Elk Licks on it and very big paths up it runs straight into the north side of an exceeding high mountain we came over that mountain that evening and camped on a small creek at the foot of it.” Robert wrote: “The 12th we were all day in the worst mountains that ever I saw, which seemed to us that we should never get out of—& there was but little to kill, & our provision was almost done—began to look a little discouraging to us, but in the evening we came to some better ground which give us more hopes, & we got meat that night plenty at the side of a laurel branch where we lay all night.”

The McAfees returned to Kentucky in 1774 as did James Harrod, whose company started Kentucky’s first permanent settlement at Harrodsburg. In his party, were Silas Harlan and his brothers. Forced out temporarily by an impending Indian war that fall, the settlers left Kentucky by Cumberland Gap, perhaps the only time that Si Harlan set foot on any of the territory that would later bear his name.

The 1770s brought a wave of settlers west both into southwest Virginia and beyond into Kentucky and parts of Tennessee. As settlements opened in the Bluegrass and continued in the valleys of southwest Virginia, men were enlisted to serve as “spies” to watch for signs of Indians so that settlers would not be taken unawares. During the period 1770-1781, John W. Porter, Richard Wells, James Fraley and Samuel Auxier each served one or more tours scouting in territory that included Harlan. Typically they were in the field from the spring to December. Wells recalled later that spying in the winter was not very pleasant: ”this cuntry lies high and for latitude in which it is situated is exceedingly cold.”

Jesse Hopkins also served in the early 1780s as a Indian ranger. On his last tour they had several skirmishes including one on the Cumberland River at the foot of Black Mountain. “At the latter place the Indians took us by surprise and killed five of declarant’s mess as they lay by his side. Declarant and the troops with him killed 17 of the Indians and took the 18th and only one left prisoner.” In May 1784, Capt. Andrew Lewis from Fort Lee at Rye Cove wrote Gov. Benjamin Harrison that “sign of about thirty Indians were seen on the Black mountain making towards this settlement.” However, as local residents and militia had dealt effectively with an earlier party, firing on them on four different occasions over four days, Lewis concluded that “being handled so roughly, I expect will make them cautious of coming into the settlement in small parties.” From his description of the state of affairs that month, this could well have been at the time of the encounter described by Hopkins.

One of the more entertaining stories of early Harlan County, and one which borders on the mythical, involves Daniel Boone. During the period after his abortive attempt to settle in Kentucky in 1773 and while he was living at Moore’s Fort in the Clinch River valley, Boone went hunting on the Kentucky side of the mountains with a companion named Yokum. As they came up Cumberland Mountain, Boone spotted “fresh Indian signs.” Positioning Yokum as a rear guard, he advanced up a hollow to check things out but was captured by the Indians before reaching the top and taken to their camp at the present site of Evarts. They brought Yokum in soon thereafter. It was decided to burn the two at the stake. In a desperate move, Boone whispered instructions that were to save their lives. When the Indians came to take them, Boone leaped on a stump and crowed like a rooster. Yokum bent over and scratched like a hen. This amused the Indians who, after a couple of repeat performances, decided to allow them to run the gauntlet. They went through the line crowing and scratching until about midpoint when they dropped their act and took off running, making a successful escape. This is said to be how Yocums Creek got its name.

Other encounters with Indians did not turn out so well. Catrons Creek is associated with an early attempt at settlement prior to 1782. (A land entry from that year includes “Cathrens improvement.”) Tradition says a man named Catron built a cabin close to the mouth of the creek on the west side; he and his son were killed by the Indians and were buried nearby.

One of the better known stories of Indian encounters in the county is the story of Fanny Noe. There are several slightly different versions of this story; what follows is a composite. At the time of settlement, the Catrons Creek valley was a canebrake from the mouth to its head. Fanny’s family built a log house with a loft in the brake. Due to the house being low to the ground, Indians were able to slip into the loft from outside. Once inside, they would play pranks on Fanny’s mother such as cutting the threads on her loom or the yarn on her spinning wheel. The children would be blamed and get punished. One fateful day the Indians, aware that the father was away from the house, swooped in, killed the mother, scalped the children and set fire to the house. Fanny, then 4 years old, managed to crawl to the safety of a nearby cornfield where she remained concealed for several days. When neighbors got there, they saw tracks indicating that there were one or more survivors, but when they called, she remained quiet as she thought the Indians had returned. Finally, she was found; she survived though she wore a cap on her head the rest of her life to hide her terrible scar.

Sang hunting, which was an economic lure bringing people into the county, was not without its perils. In June 1788, a party of ginseng hunters was attacked on Black Mountain. They had made a camp on Clover Fork as a base for their prospecting. Oral tradition has it that one day they crossed to Poor Fork to fish. When they got back that night, they heard hooting. One of the party, Thomas Lovelady, said it was not owls, it was Indians. However, the others did not believe him. Taking no chances, Lovelady concealed himself in a log and thereby escaped when the Indians closed in. A letter reporting the incident to the governor identified the victims as three members of the Breeding family and an Elam, all from New Garden, plus Neale Roberts from Glade Hollow. Breedens Creek is said to have gotten its name from this encounter.

With the close of the Revolutionary War in 1781, the push into Kentucky heightened. About this time, the first settlers and speculators appeared in Harlan County, all interested in acquiring land. Under Virginia land law, the first step in the process was to get a land warrant entitling one to take up a piece of unclaimed land.

Land warrants were used as a means of paying soldiers during both the French and Indian War and the Revolution. One could also buy warrants out right. Once a warrant was in hand, a suitable tract had to be located and entered. Assuming no one else had entered the same piece (not always easy to determine), the land had to be surveyed and then a patent would be issued. While some of those obtaining warrants located the land themselves, others, notably speculators, employed “land locators” to do the work.

During the 1780s, a number of entries were made for land in what is now Harlan County.

The first of these came on Jan. 22, 1782, Jacob Myers, a noted land locator and speculator, entered a thousand acres “lying on Cumberland River on the north side of the road that leads from Kentucky to the Settlement about 12 miles including the three forks of said River on both sides & down for quantity.” This was the present site of Harlan. On March 26, John Latham made 12 entries ranging from 250 to one thousand acres each at various sites on Brownies Creek, Cranks Creek, Poor Fork, Clover Fork, Pucketts Creek and Catrons Creek. Also on March 26, William Ewing entered 235 acres at the mouth of “Cranks Gap Creek.” In July, Isaac Winston entered land on each of the three forks adjoining the Myers entry; this land was later assigned to Aaron Fountain, who received a patent for it in 1796.

One of Winston’s entries included what a century later would be known as Skidmore Farm and two centuries later as the site of the Village Mall shopping center.

George Brooke entered a thousand acres on Martins Fork five miles above the junction “to include two Cabbins a small dedning.” Robert Mosby entered acres adjoining Brooke and Myers, and James McGavock entered 1,500 acres adjoining Brooke including “a meat house & a buckeye tree marked C.O.” The meat house most likely was a structure erected by hunters for drying meat and does not suggest a settlement. The next year George James made an entry on Martins Fork adjoining McGavock. On June 3, 1784, Richard Noel made two three thousand acre entries adjoining Latham’s land on Cranks Creek and the Cumberland River. Edward West made two entries adjoining Noel on the Cumberland River. Additional entries followed: by John Gass in 1788, Robert Sale in 1789, and John Bailey in 1790.

These men were largely interested in the land as an investment rather than for personal settlement. George Brooke, for example, was the treasurer of Virginia and lived in King and Queen County near the coast. James McGavock was a prominent citizen of southwestern Virginia living near Max Meadows and Fort Chiswell and had served as a justice of the peace for Botetourt and later Fincastle Counties. John Latham was a justice of the peace in Washington County. Isaac Winston lived in Culpeper County; his wife was Dolley Madison’s aunt. Few, if any of these men, actually set foot on the land, or personally made the entries, employing land locators to assist them by finding and entering the tracts on their behalf.

The process of taking up land in southern and southeastern Kentucky was complicated by the distance from the Lincoln county seat; at the beginning of the 1780s, the county court was located at Fort Harrod and after 1786 at Stanford. The volume of work and the complications of travel caused surveys to be delayed for several years. The first survey carried out in Harlan County was for the Myers entry in April 1786. Walter Preston, a deputy surveyor for Lincoln County, did the actual work which was reviewed and approved for recording by James Thompson, the county surveyor. In 1788, Preston returned to the area in March and surveyed 11 tracts for John Lathim and Christopher Acklin, another prominent Washington Countian to whom Latham had sold several of his entries. The Noel, West and Sale tracts were surveyed in November 1795 by Deputy Surveyor William Henderson. He did additional surveys in 1796, 1797 and 1798, at which time he completed surveys for all the entries made in the 1780s. There was also a time lag in issuance of the patents though not as great as between entries and surveys. This difficulty of getting title to one’s land due to the size of the county and the distance to the county seat undoubtedly played a role in the push to create new counties around the state in the years immediately following statehood.

Permanent settlement of Harlan County began during the second half of the 1790s. One factor in the delay undoubtedly was security. Settlers living in the territory now included in Lee, Scott and Wise counties faced a continuing threat from Indians, primarily Cherokees, a threat they dealt with in part through a string of stations or forts that afforded protection when needed and an active militia system. To settle in southeastern Kentucky was to place oneself in a vulnerable situation cut off from immediate help from government. Treaty-making with the Cherokees (Treaty of Holston, 1791) and the Shawnees (Treaty of Greenville, 1795) along with the death of a Cherokee raider named Benge in 1794 had the effect of eliminating any significant threat to the general safety of settlers in the region. While there is evidence of Indian activity in Harlan County at the time the first permanent settlers arrived, such activity was on the wane.

Virginia McClure’s study of the settlement of Appalachian Kentucky shows that the movement into Harlan County was part of a larger movement that took off in the nineties. As central Kentucky filled up, people began to realize that there was also good land to be found in the mountains. McClure found that those moving into the mountains were not the less successful remnants of the first wave who dropped out along the way as has sometimes been claimed, but individuals who were intentional in their efforts. Indeed, considering the challenges of the mountain terrain, they were undoubtedly highly motivated. They sought the river bottoms and valley floors, not the heads of hollows, because they intended to have a decent living from their farms.

These first Harlan Countians came primarily from Virginia. Many of them had been living within 75 miles or so of their new homes so it was not an extreme move. They crossed the Cumberland Mountain using some of the lesser gaps coming down Cranks Creek, Martins Fork, Clover Fork and Poor Fork or by way of Cumberland Gap going up the main river or Straight Creek or sometimes through Pound Gap and down Poor Fork.

None of the folks who settled in what would become great Harlan County is listed on the Lincoln County tax list for 1799 though that does not mean they were not here. Samuel Howard, Andrew Howard, Vincent Hobbs and Jacob Grindstaff served as chain men on surveys made in the county in 1798. In 1799, Samuel Howard made a deed to one of his sons for property in Lee County, in which he gives his residence as Lincoln County, Kentucky. Howard, George Brittain and Stephen Jones all disappear from the Lee County tax list after 1797 which supports a move to Harlan County at that time. The first tax list for Knox County in 1800 lists over 20 individuals living in what became greater Harlan including John Blanton, William Blanton, George Brittain, Parks Brittain, Lewis Green, Christopher Hobbs, Ezekiel Hobbs, Vincent Hobbs, Samuel Howard, James Howard Sr., James Howard Jr., several Joneses including Stephen, Edmund, John and Waymon, several Hoskinses including John Sr. and Thomas, as well as Edmond Osborne, William Spurlock, Stephen Taylor, William Turner and Edward Wilburn.

The list expanded rapidly over the next few years. Of those appearing on the 1800 tax list, George Brittain and William Turner between them owned four slaves who represent the first people of African origin to come to the county to live, albeit involuntarily. In 1801, the Knox County Court made grants of land based on actual settlement to nine men living on Martins Fork or one of its tributaries: Gabriel Jones and William McCraw at Cranks, James Noe and Edmund Osborne on Crummies Creek, Parks Brittain at Turtle Creek, Tryon Gibson at “Crackling Gourd,” Stephen Farmer at the Sweet Gum Bottom, Martin Comer at the mouth of Molasses Branch, Solomon Osborne on Wiley Jones Branch. On Clover Fork, grants were awarded to John Jones at the Bee Bottom, Stephen Jones, William Holloway at the Ages Bottom, and Jesse Holloway and Samuel Howard received land at the three forks. Grants made during 1802-1805 show additional settlement on Clover and Martins Forks plus the extension of settlement to upper Poor Fork (Jonathan Smith, Matthew Harris, and Richard Wallace) and down the river (Adron Howard, Jesse Brock on Wallins Creek, and Lewis Green on Pucketts Creek). Each subsequent tax list shows more names, including those of many families who would become prominent in the county’s history.

As the county’s history began to be written down in the 20th Century, two families were singled out for recognition as being “the first” to settle. Carr Bailey, a native of Westmoreland County, is said to have visited Clover Fork in 1790 and moved permanently to the area around 1795 along with two daughters and their husbands, George Brittain and William Turner. Eugene Rainey’s history of Evarts states: “Mr. Bailey wrote in his diary that he was coming to a secluded spot like Evarts to seek peace. Having gone through the War of the American Revolution, forever more he wanted to avoid war and all forms of strife.” As Bailey appears on tax lists of Lee County during most of the 1790s and not on the Knox County list until 1802, there is a possibility that he did not emigrate until after his sons-in-law had established themselves. The Turners, William and Susannah, did settle on Clover Fork, and their daughter Nancy, born in 1795, was recognized in the 1930s by the Mountain Trail Chapter of the Daughters of the American Revolution as “the first white child” born in the county. George Brittain, who was married to Bailey’s daughter, Mary, is shown on the Lee County tax lists through 1797 and seems more likely to have moved here around that year along with two of his brothers.

Samuel Howard is also frequently credited with being the first permanent settler in Harlan County and his son Wilkerson with being ‘the first white child’ born in the county, but evidence suggests a more accurate statement might be “within the present town of Harlan.” Howard served in the Revolutionary War and was with Washington at Yorktown. Tradition says that he and his wife Chloe moved their family to Kentucky in 1796, settling in the valley where Harlan is now located. They lived temporarily under a rockshelter formed by the cliffs at the confluence of Martin and Clover forks. A son, Wilkerson, was born there in 1797. Later they built a log house at the foot of Ivy Hill near the point where present day Ivy Street becomes Marsee Drive.

The Howards had several close calls with the Indians as they settled in. One day one son went to the spring to wash up. Placing his hat on a log, he was startled to see an Indian hiding behind it. The Indian lunged towards him, but the boy spun away, racing some 75 yards before losing his pursuer. Returning to the house, he roused other members of the family to come, but the Indian had disappeared; so had the hat. On another occasion, Hannah Howard, one of the daughters of the family, was going to milk when two cows got into a fight. They crashed into a rail fence causing the Indian who had been hiding there to spring up. He ran into the woods, and Hannah escaped unharmed.

Chloe Howard also had a close call with an Indian. While calling her cow one morning, she glanced down from the log where she was standing and spotted an Indian stretched out on the ground facing away from her. Having the presence of mind to pretend she hadn’t noticed him, she stepped down and began moving towards the house while continuing to call. “The nearer she got to her home, the faster she ran.” When the males of the family went to look for him, he had disappeared. Apparently he had been watching to see if there were any men around; had there not been, there might well have been a raid on the Howard house.

Building a home in the early days was challenging. To build a log cabin or house required both felling trees and raising the logs to form walls. This took muscle power that was not always available, so initially there was some improvisation in coming up with shelter. When George Burkhart, a Revolutionary War veteran from Pennsylavnia, brought his family to Cranks Creek around 1803, he first housed them in a hollow sycamore tree reported to have been large enough to allow a fence rail to be turned in it and to accommodate two beds. According to Elmon Middleton, the tree was actually a stump which he roofed with shingles. The family at that time is said to have consisted of George, his wife Sophia, and five or six children. Their son, Isaac, was born in 1806 while they were still living in the tree. To protect themselves and their herd of sheep, they built a fence of brush around the tree. At night the sheep were confined behind the fence; during the day, they fed in the mountains. One day a bear went after one of the sheep which jumped the fence. Rearing up, the bear attempted to break through, but thinking quickly, Mrs. Burkhart ran for her husband’s hog rifle and shot it dead.

By the end of the 1790s, the population of southeastern Kentucky had grown to the point that residents wanted a county of their own; they did not want to have to travel to Stanford to do legal business, and they wanted officials who were local. In 1799, the General Assembly created Knox County out of the southeastern corner of Lincoln County. At the time of its creation Knox had a population of 1,109 of whom 1,044 were white and 65 black (sixty-two of whom were enslaved). On June 23, 1800, the first county court for the new county assembled at John Logan’s house. The officers appointed by Governor James Garrard on December 21, 1799, took the oath of office. They included James Mahan, George Brittain, John Reddick, John Ballinger and Jonathan McNiel as justices of the peace and Alexander Goodin as sheriff. Brittain was the only one of the group to reside in what is now Harlan County. In October, the court accepted a gift of land from James Barbour that became the county seat.

One of the important responsibilities of county courts at the time was to lay out and oversee a road system for the county. The first business directly concerning the Harlan end of the county came in January 1801 when George Brittain made a motion to lay out a road from Crank’s Gap to the road running from Cumberland Gap to Barbourville to intersect with it between “the foard of Cumberland River” and Alexander Stewart’s house. Brittain, along with Vincent Hobbs, John Asher, Samuel Howard and William Spurlock, reported the route for this road: “Beginning at Cranks Gap running near the old trace to the Junction of the three forks of said Cumberland River, thence crossing the Piney Mountain so as to fall on the head or principal branch of Strait Creek and so on down to the mouth [modern Pineville] which said rout they conceive a good roadway may be got.” One reason for its going down Straight Creek may have been to connect with a road from the saltworks in what became Clay County. In June, a second road was laid out; this one ran from Samuel Howard’s property at the three forks up Clover Fork to the mouth of Yocum Creek and on to the Stone Gap on Cumberland Mountain. William Turner was named overseer of this road.

In 1805, the court ordered David Ross, Abner Lewis and David Smith to lay out the county’s first road up Poor Fork starting at its mouth and extending to Richard Wallace’s [modern Cumberland]. In 1808, a road was laid out from the mouth of Straight Creek to Jesse Brock’s on Wallins Creek running along the Cumberland River and going by the Laurel Mountain (later known as Tanyard Hill). In 1809, James Colston, John Colston, Gilbert Kellums, Ninian Hoskins and John Chumley were ordered to lay out a road from Cumberland Gap to the three forks. In 1811, William Day, William Gilbert, Robert Reed and Leonard Branson marked a road from the mouth of Looneys Creek to the top of Big Black Mountain. Gradually a county road system began to emerge in Knox County’s eastern end.

During the first two decades of its existence, Knox County grew rapidly, creating pressure to divide it into more manageable parts, since Kentuckians tended to believe it was their right to be within a day’s ride or so of the courthouse where not only was justice dispensed but marriage licenses issued, deeds recorded, and other government business transacted. So, this was most likely the motivation behind the petition formally received by the Kentucky House of Representatives on December 16, 1818, from “sundry citizens of Knox praying a new county may be formed therein within the boundaries proposed in said petition” and referred by it to the Committee of Propositions and Grievances. Three days later on the 19th, a petition from some residents of Knox County “remonstrating against being stricken off from the county of Knox” was also received, read, and sent to the committee which suggests that not everyone was not of the same mind about the proposal. Based on subsequent adjustments to the Harlan-Knox line during the 1820s and 1830s, the dissidents most likely lived in the section near the mouth of Straight Creek and Cumberland Gap. As the petitions appear not to have survived, we cannot say definitively.

The committee reported back to the House on Dec. 30, reporting that the request for a new county was reasonable, so the House ordered the bill brought in. It received its first reading the next day and its second on Jan. 20 when it was amended, perhaps to address the concerns of those who did not want to leave Knox County. On January 21, 1819, the bill was brought up again, was passed, and sent to the Senate which approved it two days later. Lieutenant (Acting) Governor Gabriel Slaughter gave final approval with his signature on Jan. 28, 1819. Styled “An ACT for the division of Knox county,” it opens as follows:

“BE it enacted by the General Assembly of the Commonwealth of Kentucky, That from and after the first day of April next, all that part of the county of Knox, contained in the following bounds, to wit: Beginning at Cumberland Gap, on the Virginia state line, and running thence in a direct line to the mouth of Straight creek; and thence a due north course to the present line of Knox county, and with the same, including all the heads of Cumberland river; and thence with the present line of Knox county to the beginning, shall be one distinct county, called and known by the name of Harlan.”

A number of books and websites today perpetuate an error from 19th century histories of the state that said Harlan was formed out of parts of Knox and Floyd, though it is clear from the text above that the county was formed from Knox alone.

The county was named for Silas Harlan, one of the heroes of the last great battle of the Revolutionary War in the west, the Battle of the Blue Licks. Born in 1753 in what is now West Virginia, Si came to Kentucky with James Harrod in 1774, served under George Rogers Clark in the Illinois campaigns against the British as well as in campaigns against the Shawnees. Clark is said to called him “one of the bravest and most accomplished soldiers” with whom he had served. Harlan died leading the advance party at the Blue Licks in August 1782. No details have survived as to how the name was chosen. The three counties formed immediately prior to Harlan were named for men who died in the War of 1812 as were the other three created in 1819. Two of those created the following year were also named for men who died at Blue Licks suggesting that the legislators were of a mind to remember the state’s fallen heroes.

The act directed that the justices of the peace to be appointed by the governor meet at Samuel Howard’s house at the “Three Forks” on the fourth Monday in April (in 1819, April 26) to take the oath of office and elect a clerk. Thereafter, County Court would meet on the fourth Monday of every month with the exception of May, August, and November. In those months the 12th district circuit court would convene in Harlan, for a session lasting up to six days. Knox County officials were to finish business begun by them within the territory of the new county prior to to April 1, and the Knox County Court was to appoint the tax commissioners for Harlan for 1819. Harlan’s first justices were to choose as soon as possible a site for the county seat and have the needed public buildings constructed.

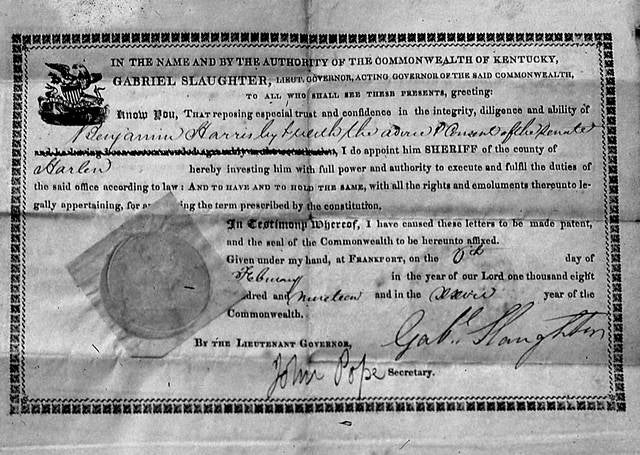

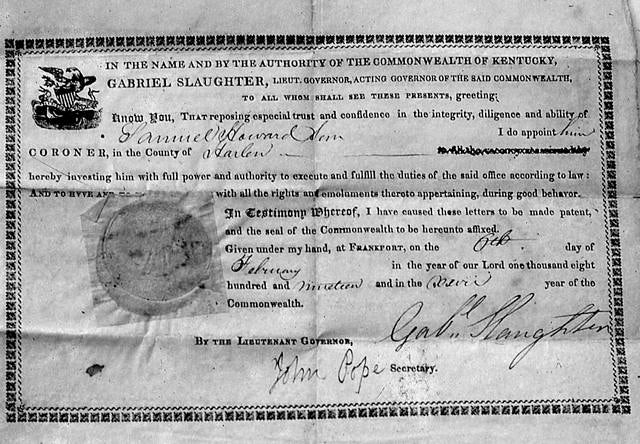

On Feb. 6, 1819, Lieutenant (Acting) Governor Gabriel Slaughter appointed seven men as the first justices of the peace for Harlan County: George Brittain, Abner Lewis, Golvin Bailey, William Taylor, Elisha Green, William Jenkins and John Noe Sr. Benjamin Harris was named sheriff and Samuel Howard Sr., coroner. In some works published in the first part of the 20th Century, Harris’s last name is given as Horn, but this is due to a misreading of the handwriting in Slaughter’s Executive Journal. The name in the record of confirmation in the Senate Journal is Harris.) Four days later, following passage of an act authorizing Harlan County to have two assistant circuit judges, Slaughter appointed George Brittain and Abner Lewis to the positions. Brittain declined the position and was replaced by Andrew Craig. The wording of the act suggests that the General Assembly was making an exception in creating these posts as it had previously abolished the office statewide. Since circuit judges, as the name implies, did in fact ride from county to county to hold court, this exception may have recognized the difficulties of travel in the area at that time.

Most of these men had settled in Harlan County by the end of the first decade of the century. Some had previously served as justices of the peace for Knox. Brittain had represented Knox in the General Assembly and had been and at the time was a general in the state militia. Several of them had known each other in Virginia prior to coming to the county, and some had ties by marriage. Brittain and Bailey were brothers-in-law. Harris’s sister was married to Noe’s brother. Howard’s son was married to Lewis’s sister. Their homes were scattered across the county: Brittain and Harris lived on Martins Fork, Bailey on Clover Fork, Lewis and Jenkins on Poor Fork, Howard at the junction of the forks. Green and Taylor on the main river, and Craig on Yellow Creek. Bailey, Brittain, Howard and Craig were slaveholders; Brittain was the largest slaveholder in the new county, owning 14. Craig had previously served as one of the state-appointed managers of the Turnpike and Wilderness Road, the main north-south route in Kentucky. These were in essence Harlan County’s “gentlemen of property and standing.”

Despite the legislative mandate and subsequent gubernatorial actions, the county was not organized as called for in 1819. In his application for a Revolutionary War pension, Henry Smith recalled “that from some cause the officers appointed to organize the County of Harlan refused to accept any appointment and for one year after Harlan County was taken off of Knox there was not a Justice of the peace or civil officer of any kind in the limits of the County.” This is also borne out in a short letter from George Brittain to the Kentucky auditor of public accounts in November 1820 explaining his tardy submission of the 1820 tax list to the state: “It has so happened by the neglect of the Different commissions for [said] county.”

To deal with this, the General Assembly on Feb. 4, 1820 approved “An Act to add a part of Knox County to Harlan County, and for other purposes.” The county line was adjusted to run from the mouth of Straight Creek to a point on the Tennessee line five miles west of Cumberland Gap. The “other purposes” were to assure that the county was indeed organized as intended. “[I]t shall be lawful for the justices of the peace and other officers heretofore appointed in and for the said county of Harlan, to take the oaths of office prescribed by the constitution and laws; and shall thereupon proceed to appoint a clerk and other officers…which the constitution authorises the county court to appoint; and to hold their courts in and for said county, as is directed in the act entitled ‘an act for the division of Knox county.” To prevent confusion as to the legality of surveys and marriages, the act affirmed that any surveys carried out during the past year in Harlan County by the Knox County surveyor or any marriages performed in the county by a justice of the peace of Knox County were legal.

As no order book prior to 1829 has been found, we do not have a record of that first meeting of the court, but it had to have met no later than April 1820 as a deed was made that month from John Howard and Samuel Howard Sr. and their wives to the County Court of Harlan selling a tract of just over 12 acres to the county for five dollars “to us in hand paid,” This tract became the county seat, a town known for much of the 19th Century as Mount Pleasant, but, which due to there being a post office elsewhere in the state with that name, soon developed an alter ego as “Harlan Court House.” An oral tradition shared by “Tiger” Howard with Dr. E.M. Howard at the time of the creation of Resthaven Cemetery said that the justices considered three possible locations for the county seat, all apparently driven by the desire to have the courthouse placed on a summit. One of these was the present site of Resthaven with the courthouse to have been where the M.W. Howard dome now stands. A second proposal was the mound on George Brittain’s farm which was located approximately across from present day Sunny Acres (the mound was removed in the late 20th century). The third was the site ultimately chosen at the junction of the three main forks of the Cumberland River. As most people in the county would have to pass through that site to get to either of the others, the justices decided in favor of centrality. Also, the valley seemed capable of supporting a town, and there was the Indian mound by the river that would be an ideal place for the courthouse.

The town as originally platted had two streets: Main Street which ran north-south to Clover Fork, and Clover Street which ran east-west parallel to the fork. Clover Street stopped at its junction with Main. The public square was located at the intersection of the streets on the northeast corner directly across from the site currently occupied by the Harlan Center. (Mabel Condon and Ralph “Castle Rock” Smith in some of their writings placed the original square on the Center site, but this is not borne out by either plat or subsequent deeds.) There were six lots of approximately a quarter acre each lying on the west side of Main, a block of twelve fronting Main and Clover Streets on the north and east sides of the public square, and two rows of fifteen extending east along Clover Street ending in the general vicinity of where Third Street joins Clover today. There was apparently at least one public sale of town lots as there are references in several deeds to “the lot purchased…at the sale of said Town lots” The first of these is in a deed from the court to George Chappell in 1821 who paid twenty-eight dollars for Lot No. 7, on the corner of Clover and Main across from the public square. Quite a few lots were sold on May 19, 1823, suggesting a public sale might also have occurred on that date. Mount Pleasant was not incorporated at the time and remained so until April 15, 1884. In 1912, it was reclassified as a fifth class city and the name changed to Harlan. An 1833 gazetteer of the United States identified the town as the southeastern most county seat in Kentucky whose “situation is elevated, mountainous and romantic.”

Mount Pleasant, Lewis Collins informs us in his 1847 state history, “received its name from the high mound or Indian grave yard on which it is built.” At the time when settlement began, cane covered the mound and valley floor, and centuries old walnut and poplar trees were growing on the mound’s summit. On the public square laid out on this mound, the county erected its first public buildings in 1820. The courthouse sat to the front of the square and most probably fronted Clover Street (a court order in 1829 called for “a ditch..on the front side of [the court] house near the Clerk’s office” to be filled with stone). The clerk’s office sat towards the back of the lot on the Clover Street side with the jail across from it in the corner farthest from the street. These buildings were built of logs, which helps explain why there were three separate structures. Concern about fire might also have been a factor. Samuel Howard helped build the jail; there is a record from December 1820 of his assigning the $249.50 due him to a creditor. Samuel Mark built the clerk’s office (in 1829 he received $52.04 due on the balance). In the absence of court records, one can only speculate both about the dimensions and the appearance of the courthouse which would have been used only for holding court and for public meetings. In 1830, glass was put in the windows, shutters hung, and a stove pipe installed. Oral tradition has it that those attending court in cold weather used heated sandstones to keep warm. Public stocks and a whipping post were added to the square in 1833.

At its November term in 1836, the county court decided to tear down the log courthouse and replace it with one to be made of brick. Based on the specifications approved by the court, the new building was 32 feet long and 24 feet wide with two stories. On the first floor, there were four 12-foot square rooms, each with a window and fireplace; the courtroom was twenty by twenty-four feet, with a single window and outside door on the front and back and two “twenty-four light” windows on the end. The interior walls were plastered and white-washed. November 1, 1838 was set as the date for completion. According to Mabel Condon, the bricks were baked at a kiln set up near the present site of the Harlan United Methodist Church. This courthouse would serve until 1863, when it was burned, apparently in retaliation for the burning of the Lee County, Virginia courthouse by Union troops. After the war, a frame courthouse was constructed on the same site but was replaced in 1886 by a brick courthouse built on the site of the current stone courthouse which replaced it in 1922.

Construction of the 1836 courthouse opened a door for local residents to the prehistory of the county. As workers dug out the foundation, they discovered “bones, pots, pipes, beads, tomahawks, and other relics of the aborigines of the country, at about three feet from the surface of the earth. It was then concluded that it would be best to remove the mound entirely, which covers between a quarter and a half an acre from eight to twelve feet in depth. In proceeding it was found that it was covered with strata of bones from one extremity to the other. Human bones, from full grown size to the infant, were found in abundance.” The dead had been buried heads oriented to the east and bodies arranged in a sitting ‘posture.’ This so intrigued some of the community that a local lawyer wrote letters to downstate newspapers inquiring as to whether someone could shed light on the discoveries. The tools and pottery found, he wrote, “evince ingenuity and skill.” Particularly striking was a half-gallon pot “superior in durability to any of our modern ware” and decorated with “little rough knots, near an inch in length.” The pipes dug up “are precisely shaped like the most commonly used pipes in Kentucky, but are highly polished and neatly carved.” Over the years to come, the mound would yield further discoveries, in particular in the 1930s during construction of the buildings that front Main Street at that point. Current knowledge suggests it was built by members of the Adena culture during the Woodland archaeological period (1000 B.C. to 1000 A.D.).

Harlan County in 1820 had a population of 1,961 of whom 1,851 were white and two, free blacks. There were also 108 slaves distributed among twenty-two owners. The population as a whole was young; 74 percent were under 26. Of the free population, 58 percent were under 16 and of the slave population, 54 percent were under fourteen. 492 Harlan Countians (including the slaves) were reported as employed in agriculture, one in manufacturing, and none in commerce. There were no “foreigners not naturalized” in their midst. If there were any Indians, their presence was not recorded by the Census as they were not taxed. By 1850, the population reached 4,208 of whom 4,108 were white, 37 free blacks, and 123 slaves. There were still no foreign born. The adult literacy rate for the free population stood at 80.3 percent, which was up from 1840 when it was 76.9 percent. This is interesting considering that the total expenditure for public schools in the county was then $505 per year.

Beginning in the late 1820s, the General Assembly appropriated money in the form of land warrants to be used by local commissioners to improve roads in the county at various locations. In January 1829, 10,000 acres in warrants were appropriated for roads from Cumberland Ford to Mount Pleasant and the Virginia line and up Poor Fork which was supplemented in 1834 with a grant to improve the road from Mount Pleasant to Crank’s Gap and one in 1836 to rebuild the road around Laurel Hill (Tanyard Hill). Appropriations in 1831 and 1833 sought to improve the road from the mouth of Straight Creek to the Red Bird saltworks in Clay County including construction of a bridge at the mouth of the creek. Appropriations were also made to improve roads from Manchester to Mount Pleasant via Dillon Asher’s, from Perry County to Poor Fork via Hurricane Gap, and from Cannon Creek to Laurel. At the same time that the legislature was handing out funds for some roads, it authorized the county courts in Harlan and other southeastern counties at their discretion to reduce the width of lesser roads to not less than five feet. The court then reduced roads in the county to 15 feet in width.

By the 1830s, the two main roads through the county were the one heading up the Cumberland from Cumberland Ford to Mount Pleasant and on to Jonesville via Martins Fork and Cranks Gap and the one coming from Hazard over Pine Mountain to the site of modern Cumberland and on to Estillville, Virginia( now Gate City). An 1839 map characterizes these roads “a 1 Horse Mail or Sulky Road” as opposed to a 2 Horse Mail Stage Road or a 4 Horse Mail Post Coach Road.” At that time, the section of the road from the mouth of Poor Fork to the Hazard road was labelled a “Gross” road. An 1856 map shows these roads and also a road from Perry County to Harlan via War Gap. However, the state geologist who visited the county around that time called it “a bridle path.” The two mail roads served as postal routes. United States Post Office bid requests from the late 1830s describe them. Mail was to leave Cumberland Ford at 6:00 a.m. on Mondays for Jonesville, Virginia, arriving there by 11:00 a.m. on Tuesdays with stops at Letcher (a post office near modern Page) and Harlan Court House. The return trip would begin on Tuesdays at 1:00 p.m. reaching Cumberland Ford the next day by 6:00 p.m . From Hazard, mail would go “by Carr’s fork, Mouth of Leatherwood creek, Hezekiah Branson’s in Harlan county [Cumberland], and Stone Gap to Estillville, Va. 75 miles and back once a week.” The contractor would be allowed 36 hours to make the trip between the two points leaving Hazard at 6:00 a.m. on Saturdays and arriving in Estillville by 6:00 p.m. on Sunday, then starting the return run on Monday at 6:00 a.m. ending at 6:00 p.m. on Tuesday. These mail routes were the county’s principal connection to the outside world.

Farming was the county’s main economic activity prior to the Civil War with corn being the principal crop. Harlan Countians also grew potatoes, beans, and peas, and oats, all primarily for home consumption. For cash, Harlan Countians turned to livestock. Cattle and hogs could be driven to markets downstate and in Virginia and Tennessee. While some local men did this themselves, it was common for buyers to come around and collect herds using their own employees to drive them to market. Sheep produced wool which also could be sold for export out of the county. Maple sugar, honey and beeswax, and ginseng could bring in needed cash or credit at one of the handful of local stores. Only a handful of Harlan Countians were employed in trades, commerce, and manufacturing. The county’s reputation in its early years as described by an 1850s gazetteer, rested on its mountains “with fine forests and abundant water-power; soil in the valleys productive and generally good pasturage.” The development of the county’s forests would wait until the 1870s; development of its coal resources, only then beginning to be studied by geologists, until the 20th Century when the county would be completely transformed by the advent of modern technology and an influx of people leading to the society we know today.